|

|

|

This page is dedicated to all the odd facts, strange rules and interesting customs about

the early game of base ball that we modern ballists learn to live with and take advantage of. While we try to be as authentic

as possible, we 21st Century ballists sometimes take liberties when it comes to style and knowledge, you often can't help

but blend the two...more so by accident and competative balance of the game on the field (perhaps the biggest cause) than

by disrespect. I can guarantee that there is not one team or one group out there in vintage base ball land as authentic

as they say. After all we have more than 150 years of baseball history knowledge.

Equipment

- In April of 1877 James Tyng became the first player to wear a catcher's mask in a professional game. The mask was

designed and patented by Fred Thayer in 1878. Modern day ballists will typically purchase their masks on eBay and either use

"as is" or modernize the padding and paint the cage. The style of masks that each team uses is a unique journey through early

baseball history in itself. Although it is very rare to find a mask from the 1880s (they tend to be fragile and narrow

shaped making it almost impossible to use modern padding), what you see are masks from the late 1890s to the 1930s.

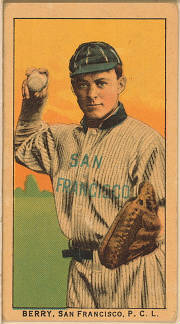

- In 1904, Claude Berry, playing for the Chicago White Sox, became the first major league catcher to wear a protective

cup. Needless to say, he was a true innovator (A big HUZZAH! to Claude).

Claude Berry

- The type of bats you see on many vintage ballists benches may look odd and different than what you see in the modern game

but there are a few errors we make to achieve the "look."

- Ball handle, "mushroom" handle, and double handle bats did not exist until the early 1900s.

- Cupped ends, although not completely modern, were not part of the 19th Century game.

-

- The catcher's gloves for the over-hand game is perhaps the most controversial part of the vintage game today. While the

use of fielder's gloves in the late 1880s game is easily confirmed, the type of or the timeline for the catcher's glove is

cloudy. What you see on the field in today's vintage game is not what you saw during that time period. We have tried to combine

safety with something that looks the part (at least it does to the casual "crank"). What you see are either replica 1920s-1940s

fielder's glove with the webbing and connecting finger laces cut. Some clubs will try to sneak in a "pancake" glove for safety

(to the catcher's hands - both of them) but this opens up a whole new chapter of issues...A) Safety for the batter (as the

pitcher can now throw harder, more often - greater chance of accidental beanings), and B) Competative balance (less pass balls,

more fast balls). We 21st Century ballists are trying to replicate a specific era of the greatest change in the game. The

mid 1880s was a time period when over-hand pitching was first introduced...the style and velocity was nowhere near what we

see today. As the pitcher's velocity and control improved, the catcher's hands began to take a beating (lack of padding and

foul tips increased causing injuries to the both the glove hand and the glove free hand normally needed to contain the ball

in the glove hand - cupping the hands in order to catch the ball was the norm, not the one hand behind the back style for

protection of today). Teams of that era would rotate catchers, game to game to allow healing time. By the 1890s, with

the velocity of pitching increasing and the catcher's gloves evolving into "mitts," the game on the field was becoming

a "battery" game between the pitcher and catcher. Scores were decreasing and interest among the fans were waning as well

(sort of like modern-day girls softball games). To address this concern, the distance between home plate and the pitcher was

moved back 5 feet 6 inches to its current distance.

Style of Play

- Head first slides were relatively new for the 1880s but make no mistake, it was done.

-

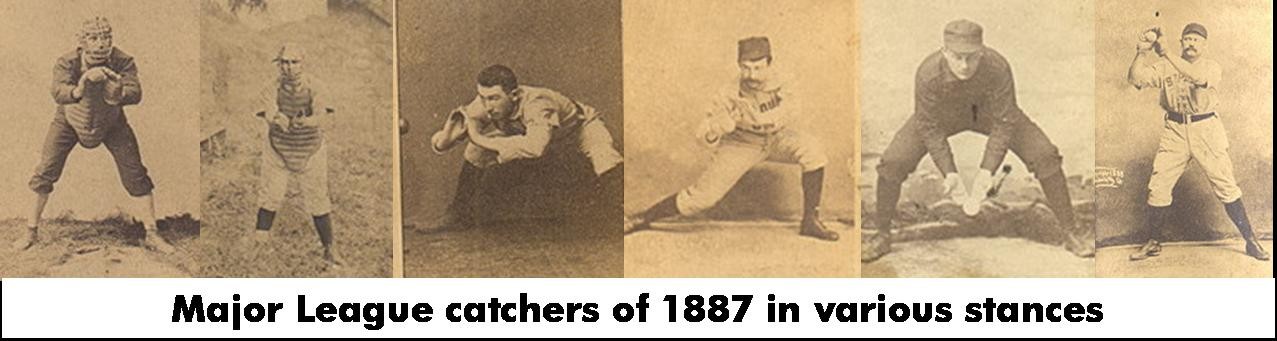

- Catchers croutching close behind home plate was not the style of the day. Typically, a catcher from the late 19th

century would stand back some 5 to 10 feet behind the plate and act almost as a goalie and knock the ball down and sometimes

take the pitch on the bounce. In order to catch or stop low pitches, the catcher would bend-down and not crouch. Once

every at-bat, the pitcher may call for (yes the pitcher called the pitches) a fast ball so the catcher would back-up another

5 feet or so. Again, competative balance prohibits extreme accuracy. Since the request for "low zones" out-number "high

zones" by the batter, stopping "low-zone" pitches in order to get strikes and prevent passed-balls is a massive challenge

for the catcher.

Rule Quirks

- Perhaps the best known of all the "work-around" rules is the dropped 3rd strike with men on base strategy. In the 1880s

on a drpped 3rd strike (by the catcher) with a man on 1st, the man on 1st is forced to run regardless of how many outs.

Ultimately, this rule allows for the catcher to drop the third strike (with bases loaded), step on home (for one out), throw

to third for a force out (for a second out) and then the 3rd baseman throws to second for another force out (a triple play!).

-

- A very legal yet very rare play would be stealing first base. With runners on 1st and 3rd, the runner at 1st

attempts to steal 2nd in order to draw a throw from the catcher to give the runner at 3rd the opportunity to score. If

however no attempt by the catcher is made and the runner from 1st is now on 2nd, the runner on 2nd can now steal back to 1st

in order to create confusion and draw a throw from the catcher and again give opportunity for the runner at 3rd to score.

This was legal in the major leagues until 1920.

-

- Another legal yet rarely acted upon play would be not advncing to first base. With a runner on 1st and an a batted ground ball

that is an obvious out making play, the batter elects to stand on home plate and not attempt to advance to 1st declaring

himself out. This removes the force out on the runner at 1st and the possible double play.

What Year Is This and What Rules?

- National Association, National League, American Association, "Base Ball Association - League - Club - Your Town U.S.A.,"

they all had rules, some similiar and many different depending on year.

-

- One of the two controversial rules used in the VBBF Playoffs and World Series was denounced by many "know it alls" by

not being 1880s. The foul ball caught on one bounce for an out was in play up to 1884 according

to the American Assciation rules.

It Was Almost 63' 8" or 65' 9"!

- During the winter baseball meetings of 1892-1893, the rules committee of the National League had been bantering

around ideas to elimninate the "pitcher's game" in order to bring back fan interest and ticket sales. A fear was growing that

the game was too much a pitchers game and not enough offense. By the season of 1892, the skill and speed of the pitchers were

very similair to what we modern day vintage ballists are experiencing with the one difference being the catchers glove.

By then, the pancake glove was in use and passed balls had decreased. Pitchers were heating up so much that offense was

nearly gone. The rules committee wanted to elimnate the pitchers box and have the pitcher pitch from dead center of the diamond

from a rubber slab, 12" wide by 4" deep. That distance being 63' 8" to the center of home plate. The plan was to also evenout

the balls and strikes to 4 & 4 instead of 4 balls & 3 strikes. The rules committee, made of of a group of team owners,

all agreed that the distance must be pushed back but some wanted it pushed back 5' not 8'. An initial vote among the rules

committee produced a tie followed by much debate and eventually it was settled on the 5' distance. Can you imagine?...63'

8"?

- ...or better yet a 93' diamond and the ability to over-run all bases and the pitcher dead center of the

diamond at 65' 9"...this was seriously considered as well.

A Fielding Coach?

- In the off-season of 1891-1892, a rule to allow a defensive coach on the field was considered. Harry Wright, Hall-of-Fame

manager and a mover and shaker of the early game, was quoted in the New York Sun, "A team in the field needs a man on the

coaching lines even more than a team at the bat."

Some of this data were sourced from the great book by Peter Morris 'A Game of Inches' and Eric Miklich's

book 'The Rules of the Game,' and Sporting Life microfilm.

We Struggle Playing Backwards

They Struggled Playing Forwards

In September of 1896 Westfield Massachusetts’ William “Adonis” Terry

would write an article for the Chicago News which also appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle regarding

the evolution of pitching regulations and its effect on the game. This is a great article for two important reasons; A) This

is in Terry’s own words, B) There was no one in the game at the time as successful as Terry who not only survived the

changes over the years but also thrived, especially in the later years of his career when the last change to the pitching

format was the most drastic. He was one of only a very few who made the successful transition of pitching from 55’ 6”

to 60’ 6”.

Born in Westfield Massachusetts, Terry began

his professional career in 1883 with the then Brooklyn Grays pitching side-arm in the pitcher’s box that all us modern day vintage

ballists are familiar with. By the time his major league career was over in 1897, he was pitching from 60’ 6”

and throwing off a rubber slab.

It is interesting to note the irony in this where we modern ballists struggle playing

backwards with the rules of the late 19th century while Terry tells of the struggles of the 19th century

ballists playing forward. To learn more about the career of Adonis Terry checkout http://adonisterry.tripod.com

Dan “Gunner” Genovese

‘Hard To Pitch Nowadays’

Adonis Terry

September, 1896

Pitching today is a very different

job from what it was twenty years ago, or ten or even five. Rules have been changed and tinkered with; distances have been

lengthened and a myriad of tricks, calculated to embarrass the pitcher, have been vainly tried. Unless the rulemakers take

into their heads to so fix the rules that the pitcher will simply have to stand up and lob the ball over the plate the pitcher

will remain autocrat of the game and batting averages will continue to be under .500.

No matter what the changes in the

rules might be, the men who were the pitchers under one style remained pitchers under the next arrangement. Some of them have

been driven out of the business by the changes from time to time, but the pitchers who survived had been pitchers before and

they have never succeeded in inventing rules which would make twirlers out of short stops or great box stars out of fielders.

Pitching under the ancient round

arm delivery was a curious process and I fancy that only the short distances prevented the pitchers from being hit even harder

than they were, and some of the old time games had scores large enough to satisfy any crank on batting. Then the pitchers

were allowed to get their arms higher and higher, until all restrictions were done away with and they could throw where and

when they wanted. The system under which the Chicago team won its glory (Chicago White Stockings won back-to-back National League pennants in 1885 & 1886) was that which

allowed the batter to call for a ball where he wanted it, high or low, and the command which this necessitated from the pitcher

was marvelous. Seven balls were called before a batter could take his base and the number was none too great under such circumstances.

During the period of the call for your ball rule an idiocy requiring the pitcher to keep both feet on the ground while throwing

the ball was perpetrated (For the 1885 season the National

League implemented this rule in order to slow velocity). If you don’t think that rule was a strain,

just take a ball and try to throw it, even with moderate speed, and keep both feet fixed on the ground. It requires a gyration

of arm and body that’s worse then seven Delsarte lessons (A popular form of expression through dance that encompasses almost gymnastic

type movements).

With the three strike and four

ball rule, originally four strikes and five balls, the pitchers began to develop great speed and fine control. Then the howl

about the pitcher domination began to be raised and the batting cranks commenced to scream about the advantage given the pitcher.

Even so, the science of batting and the art of fielding were advancing just as rapidly as the talent of the pitcher. There

were fewer strikeouts to the game in 1892, last year of the fifty feet distance, than used to be the rule in 1887. The ball

was coming in faster no doubt, but the keen eyed fellows at the rubber weren’t missing it to any great degree. It was

the work of the fellows in the field that was killing the batting. There were games where only one hit would be chalked up

for a team, and yet the winning pitcher would have only four or five strikeouts. The fielders have taken care of all the rest.

Something had to be done, however, to still the popular clamor for more batting, and, of course, the poor pitcher had to suffer.

So the box was abolished, a small strip of rubber substituted, science and change of place and pace were discouraged by compelling

the pitcher to keep his foot on that slab, and the slab itself was set back in the diamond (Interestingly, Terry would comment in an earlier

article in February of 1895 that some of the early struggles and cheating pitchers would perform with the rubber. With the

rubber, being just 12” wide at the time, many pitchers would stand either far off to the left or far off to the right

of the rubber because pitchers who pitched from the rubber would create a deep hole, nearly six inches causing pitchers to

become off-balance and lose command. Umpires would rarely enforce this rule and opposing captains would never point this out.

Eventually, the rubber was widened to 24”). That worked pretty well. The slugger had a fraction more

time to judge the ball. As I said, they could hit it before, but they had to make quick haphazard snaps at the ball. Now they

have time to, at least, make an attempt to place it. The result was a most satisfactory increase in the slugging.

But all the rules ever invented

to hamper the pitcher couldn’t kill his fielders, and the men behind the pitcher have now learned to play for men under

the new rules just as under the old. Batting averages were a shade lower in 1895 than in 1894, and are quite a little smaller

so far this season. The fielders have gauged their men…that is all.

Formerly a pitcher could go in

every other day with perfect safety. Now a rest of at least two days between games is necessary, and many pitchers cannot

be worked more than one day in four. The extra distance makes a man work that much harder to send the ball up the way he used

to do. There has been a change, too, in the tricks of the trade. We used to largely rely upon great speed, with short, fast

curves, alternated with a slow ball. You can all remember the drop ball of Buffington and Ramsey, Luby’s sharp outcurve,

Keefe’s slow ball, John Clarkson’s variety of fast and slow balls (Terry cites pitchers, some Hall of Famers and some of limited

success, whose careers were, for the most part, finished when the pitching distance was moved back five feet).

Nowadays, the curves are necessarily wider and slower, and all such scientific tricks as a change of pace, keeping the ball

up around the batter’s neck and the simple process of sending it over at medium speed, straight and true, with trust

in the fielder for safety, are the proper scheme. A drop curve is hard to throw now, and a drop curve pitchers had a terrible

time the first year of the new rules, as everything they threw would hit the plate. A wide out-curve can be seen and judged

much easier than in the old days, and an incurve works rather batter. The fast, high ball, with a little raise to it, and

a drop by a man that can keep it up from the plate, are the curves of the day.

Chicago News

Brooklyn Daily Eagle

September 15, 1896

The Greatest Invention Never Used

Sourced directly from web site of the U.S. National Archives

Perhaps one of the most bizarre baseball-related inventions was the "baseball catcher" by James E. Bennett (Invention

Patent #755,209), patented on March 22, 1904. This contraption basically replaced the catcher's mitt with a wire cage placed

on the catcher's chest. The object of the invention was to protect the catcher's hands so that the hands would not come in

contact with the ball until it was time to throw it back to the pitcher. The invention was a rectangular open-wire frame body

reinforced by slotted walls of wood. The impact of the ball on the catcher's chest is protected by springs on the rear wall

of the device. After the ball has passed through the open front end, it closes automatically. At the bottom of the device

is an opening where the ball passes into a pocket where it is retrieved by the catcher. The device also includes a wire mesh

on the top to protect the catcher's face. The patent drawings do an excellent job of illustrating this device. http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2006/spring/baseball.html?template=print

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|